MY STORY

By Marc Fest

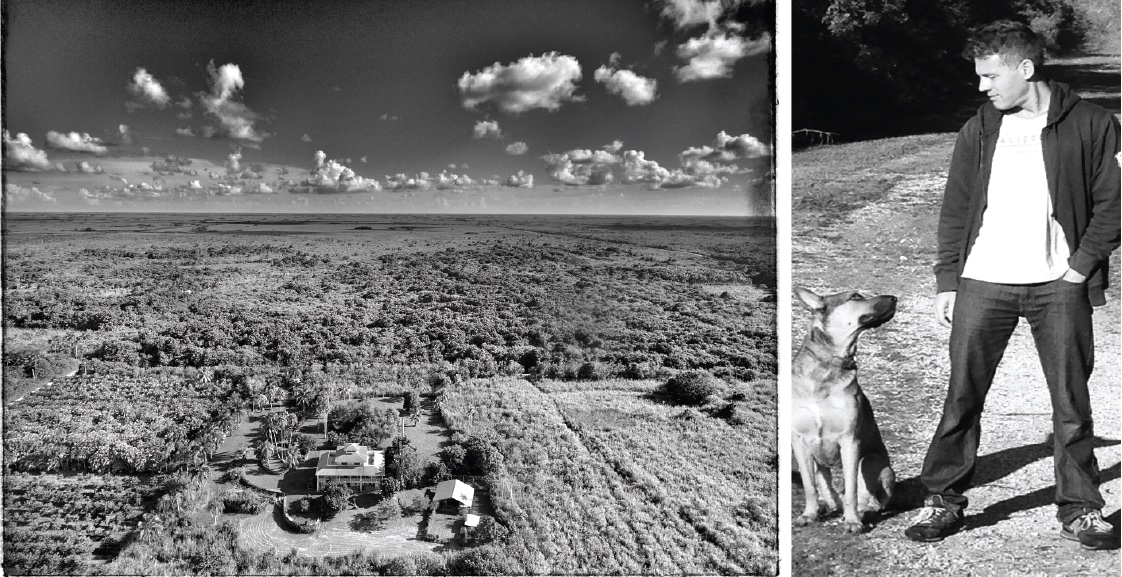

Before I see my first client, at the beginning of each day, I take my Belgian Shepherd dog Zeus out for a bike ride on the deserted dirt road that leads to our remote and flood-prone property here on the edge of the South Florida Everglades. The long ride and the solitude of the place put me in the right frame of mind for meeting with my usually three or four clients per day. They come from all across America and join me for 60-minute, one-on-one video calls in which I help them compress the stories of their struggles into a short speech that they can use in a variety of situations to get more support and attention for their work.

I call my business “Elevator Speech Training” even though it’s not just about that proverbial 30-second spiel inside an elevator. For example, I often end up helping people with the kind of round-robin introductions for participants in a conference panel. So that scenario may give you two to three minutes of speaking time. What I don’t do is long-form speeches, say, anything longer than 5 minutes. I don’t aim to be a speech writer.

I love working in a remote place. I sometimes don’t leave “the farm” as I call it for ten days straight. At the risk of sounding oxymoronic, I’d describe myself as a hermit who loves communication.

For my broadband Internet connection, I have to use a military-grade LTE modem whose directional antennas point to a cellphone tower three miles away near the entrance to the Everglades National Park. There’s no municipal water here either, so I have to use a well.

Marc

I have a formula for helping you get more attention and support for whatever you do. It works for anybody in any situation. My clients use it to succeed on the frontlines of some of the biggest challenges of our time.

They are former National Security Council officials now working at D.C. think tanks, worrying about things like the impact of artificial intelligence on the command and control systems of nuclear weapons. They are CEOs of billion-dollar affordable housing investment funds, concerned about COVID-19 causing a “pandemic of evictions.” They are transgender migrants from Guatemala who now work as community organizers to help prepare undocumented immigrants for the terrifying moment when an ICE officer will knock at their door to arrest them.

It almost always comes down to a formula of three seemingly simple things: Urgency, specificity, and emotion. The first letters spell “USE,” so I often find myself saying: “Use USE, and you’ll be doing great.”

Before each encounter, I sit down on a black leather sofa, close my eyes, and focus on my breathing for ten minutes. It helps me clear my mind. I want to be fully prepared to immerse myself in the mission and values of the person I’m working with.

I have this feeling right before every training session that I’m about to enter into a sacred realm. My clients work on do-or-die crises like climate change or averting nuclear war or fleeing unimaginable horrors. They are caring, driven, innovative and idealistic people. I really feel as if I get to see every day a cross section of the very best people our world has to offer. Even in these troubled times, they make me feel optimistic.

Clients often ask me how long their elevator speech should be. I tell them it depends. The proverbial encounter inside an elevator demands being brief indeed, say, 60 seconds or less. But when you have a chance to introduce yourself to an audience as a participant in a panel discussion, two to three minutes is a good target. If you have a one-on-one conversation at a cocktail party, it’ll be a back-and-forth that can go on for many minutes.

I landed on emphasizing “use USE” after hundreds of training sessions in which I found that my clients almost always fall short in conveying urgency, specificity and emotion. It’s natural. They are extremely busy with day-to-day work, so they talk about that instead of the urgent reason behind what they do. Hence the lack of urgency. Because it’s mentally easier, they default to only giving abstract descriptions of problems and solutions without also providing riveting and concrete examples. Hence the lack of specificity. And because they often feel awkward about sharing how they feel about what they do and why they do it, they miss out on creating an empathic connection with their listeners. Hence the lack of emotion.

Zeus

The result is that even highly experienced leaders are often not nearly as persuasive as they could be.

I am a former vice president of communications for the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the New World Symphony based in Miami. Now I primarily partner with funders who want to help the nonprofit organizations they support to clearly and dynamically communicate the importance of their causes.

My clients include some of the country’s best-known philanthropies: Knight Foundation, Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation, JPB Foundation, The Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund, and others. My company is an LLC and cannot receive grants directly, so foundations sometimes make grants for the training through a fiscal sponsor intermediary, NEO Philanthropy. NEO takes on capacity builders like me as “projects” to strengthen the work of nonprofits. Other Elevator Speech Training clients include for-profit corporations like Axel Springer, an international media company headquartered in Berlin.

These days, I’m booked up months in advance. It’s gratifying to hear clients often say they’re amazed by the progress they make “in just one hour.” For example, the CEO of a billion-dollar affordable housing investment fund told me “If only all my one-hour meetings were so productive.”

Now, with the national shutdown during the pandemic, I think my clients appreciate the opportunity to work with someone whose business had already adapted to video training. For example, one donor relations manager said to me: “As I was struggling with stress and lack of concentration amidst the rapidly changing public health situation, the training brought my mental focus back on the purpose of my work.”

I believe that my trainings are effective in part because I prepare well. By the time my MacBook Pro lights up with the face of a client, I will have looked at the person’s websites, LinkedIn page, Twitter feed, TED talk, recent media coverage, and anything else I can find online to customize the training. My being familiar with their work allows us to dive right in.

I’m aware that different clients have different needs. Communications success for nonprofits usually means raising money from potential funders. For an analyst at a think tank, it can mean briefing members of Congress on the dangers of not renewing an arms control treaty with Russia. For a community organizer, it can mean enrolling undocumented immigrants as grassroots members in an organization that fights for immigration reform.

For my clients, crafting a successful elevator speech often means that they will have much greater confidence to move forward with an important project.

I believe that I can be useful to such a diverse group of clients because of the “Elevator Speech Framework” I developed. It won’t surprise you that it includes prompts for expressing urgency, specificity, and emotion. For example, to increase urgency, it suggests beginning one sentence with the words “what’s ultimately at stake is…” It also includes prompts to begin at least three sentences with the phrase “for example.” This will automatically nudge you towards becoming more specific, and thereby more credible and persuasive.

Working with clients on expressing what’s “ultimately at stake,” can sometimes lead to new ideas for stronger messages. For example, I work with a lot of organizations in the civic engagement space. Often, their first stab at stating what’s at stake is saying things like “democracy is at stake,” or “representative government.” However, those are abstract, intellectual concepts. The Elevator Speech Framework is designed to broaden frames. So we ask ourselves: Why did our forefathers (and foremothers) introduce democracy in the first place? Right. To ensure freedom from tyranny (from a king, or some modern-day version of it). “Freedom from tyranny” is visceral and dramatic, and it will resonate a lot more with people than “representative democracy”. Suddenly, democracy is not an end in itself, but a means towards an even greater end. One that gives people goosebumps, and compels them to take action (like registering to vote).

On a lighter note, there is a lot of laughter during the sessions. My clients have called the experience “a breath of fresh air,” “really energizing,” and filled with “generosity and warm humor.”

Sometimes, Step Seven in the Elevator Speech Framework (“personalization”) will make a client cry. It’s where I encourage them to talk about why they care about their work and express an emotion. Their natural tendency is to talk about how accomplished or experienced they are, but I want them to reveal a vulnerability or a pain point that relates to their work. That makes their pitch stronger, but for some clients it is hard. But this step can be really powerful, especially right before your call to action. If you can lower your guard and share something vulnerable, then your audience will lower its guard and become much more responsive.

I could give you some great examples for how clients convey why what they do is deeply personal but I treat my engagements with a lawyer-client-like level of confidentiality. Even if I left out the name you could, in some cases, identify the person by going through the testimonials.

The strange juxtaposition of my interactions via Zoom with my reclusive Everglades existence is not lost on me. Sometimes I worry a little that it makes me a bit peculiar. For example, there’s this one yellow butterfly. She’s been coming by for months, making the same rounds every single day. Did you know that butterflies can live for up to a year? I call her Yellow. When I see her, I say ‘Hey, Yellow, how are you?’ I tried taking a photo of Yellow with my Canon. But it came out blurry. I like it anyway. Sometimes I’m asking myself: What’s happened to you that you have a relationship with a butterfly?

Yellow (blurry)